A poetry reading competition for elementary school children kicked off the Singaraja Literary Festival on a Friday early morning. While sipping a great-tasting ice cafe latte from one of the food and drink stands, passionate participants showed that they didn’t just learn the text to perform for the jury, but added strong body language to convey the message and knew exactly when to soften the voice and bring in power.

Festival director Sonia Piscayanti refers to the competition in her opening speech, saying she believes “literature and poetry remain the nation’s healers in Bali’s current difficult conditions”. She mentions how the island and Indonesia as a country, are not doing well and literature can be a sedative—if not a way out.

Singaraja was the Dutch colonial capital for Bali and the Lesser Sunda Islands from 1849 and continued to be the administrative capital until 1958. The city in the north of Bali distinguishes itself from the south where mass tourism has taken over. Sonia and her husband Made Adnyana Ole founded Komunitas Mahima in Singaraja bolstering the confidence of young and old Balinese to write and perform. They want to make the town the intellectual capital of the island, bringing all the talent to a stage for more people to recognize and enjoy.

Singaraja Literary Festival | Pic: SLF/Amri

The Dharma Pemaculan lontar is the theme of this year’s Singaraja Literary Festival translated as Mother Earth’s Energy. The manuscript discusses several topics regarding cultivating rice, from calculating good and bad times for farmer activities, stages and procedures for planting and maintaining rice, to dealing with pests, treating rice after it is harvested, and carrying out field rituals. Agriculture is positioned in the lontar as a mother taking care of all humans.

“By taking the theme of Dharma Pemaculan, the festival wants to retrace the diversity of agriculture and present it in the form of cultural diversity, exhibitions, workshops, performances of literary transformations into theater, the musicalization of poetry, and films”, Sonia explains in her speech.

Two MCs in Balinese high fashion announced the performance of the Dharma Pemaculan brought to life by STAHN Mpu Kuturan Singaraja in which modern dance, acrobatic moves, intense facial expressions, and waving palm leaves alternated in a dynamic stage setting. The choreography was professional and refined. The festival starts with a bang and this is just the beginning.

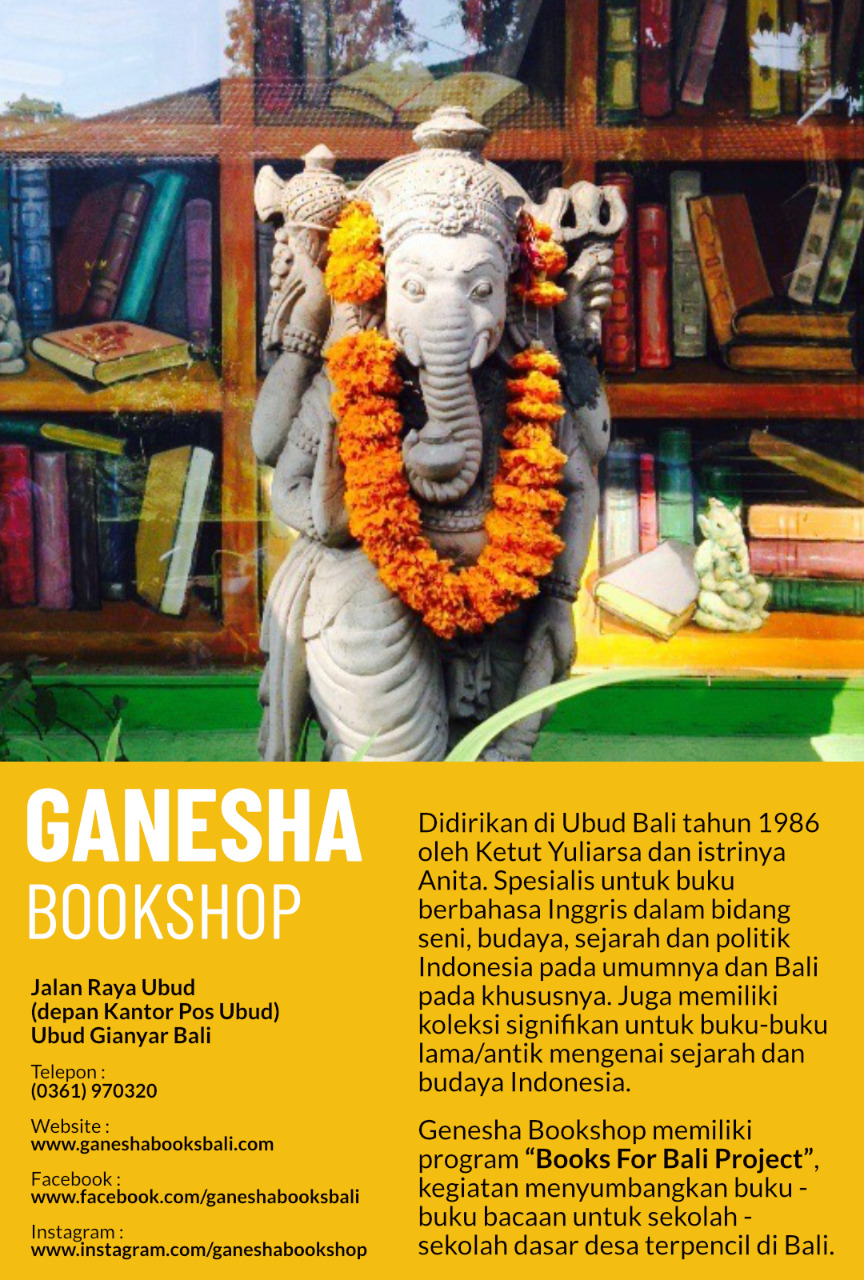

The palm leaf has a deep meaning, not just as a symbol of nature and rural life but also as the material from which the lontar manuscripts are made. The knowledgeable guide Ayu explains the history of the ancient old manuscripts that are being preserved – sometimes copies of the original – in the Gedong Kirtya library in the corner of the festival site. Four enthusiastic visitors who came from Ubud to attend the event, listened carefully and tried to write on the example lontars themselves. It’s not easy to carve text in a processed palm leaf, a small knife serves as a pen.

Singaraja Literary Festival | Pic: SLF/Amri

David, Mandy, Stephanie, and Fred participate in the program organized in collaboration with Inclusive Journalism. After the library tour, Sonia welcomes the four with the local dish tipat cantok for lunch, blanched vegetables with rice cake, and spicy peanut sauce. Under the trees in front of Museum Buleleng, the group discusses the role of Balinese women in society and the importance of literature and poetry in expressing thoughts and feelings.

The Singaraja Literary Festival is held on Sonia’s birth ground, the house where she grew up is just behind Museum Buleleng where part of the program takes place. When she as a young girl spent time with her family, it was the moments of interacting with normal people that Sonia treasured most. Her father was a social person, valuing eating and drinking together and having conversations with people on the streets. “He would have loved seeing you all here this weekend”, Sonia shared during a lunch session with tearing eyes about her dad who passed away three years ago.

She must have developed a strong awareness of her role as a woman in Balinese society when her parents took her out to mingle with others. It has become the core of her work, to assure women don’t need to be invisible and obedient. The literary language helps them to speak in a manner that is strong and confident yet subtle and non-confrontational.

The festival shows many of these females from Bali and around the country.

Like famous contemporary author and film script writer Dewi “Dee” Lestari who teaches prose writing skills to 30 young enthusiasts in a workshop in the former family compound of Soekarno’s mother, right behind the festival terrain. “Throw it all out in writing and remove the garbage in our minds. And edit later”, she tells them.

Singaraja Literary Festival | Pic: SLF/Amri

Researcher Olin Monteiro shares about the film “Women of Sumba Land” which tells the story of women on the island in the eastern part of Indonesia where old traditions regarding marriage are still being held strongly, and women are being objectified by it.

From the Asia Pacific Writers & Translators who organized the English language workshops at the festival director Sally Breen took the stage at closing night to perform a poetic complaint towards the Indonesian sex before marriage law.

And women from Papua who got raped by the Indonesian army found a voice through the performance of Luna Vidya, with the moving singing by her son Elmatu of the lyrics of “Aku”, a poem by Chairil Anwar (1922-1949).

A weekend filled with poetry performances and readings, fiction and non-fiction writing workshops, public lectures, book launches, and a children’s program, all around the theme of cherishing Balinese wisdom kept in ancient manuscripts and seeking ways to translate the knowledge to new generations and ways of living.

Media partner Tatkala published several essays in the run-up to the festival about Balinese poets being dominated for decades by the voice of anxiety about the loss of land due to massive tourism development. I Made Sujaya writes in Farmers in the Gaze of Our Writers: Then and Now how Indonesian literature has historically neglected agricultural themes, focusing instead on urban, religious, and social issues, but with exceptions in poetry and short stories highlighting the struggles and complexities of farmer life.

Singaraja Literary Festival | Pic: SLF/Amri

The complexity of the problems Bali currently faces can’t be answered by agriculture. Agus Wiratama’s essay Seeing Space Opportunities: Rice Fields and Performance Laboratories emphasizes that people want to maintain the ricefields but at the same time, the economic needs have changed. Wiratama asks out loud if the ricefield’s task as a performance laboratory is over and we need to look into the virtual world to develop further. ‘It is better to raise white cows than to grow rice without being certain of a good result’. With white cows, the Balinese refer to the elite class who turn a rice field into something foreign, bordered by walls, cutting off the water, and prohibited from entering by anyone.

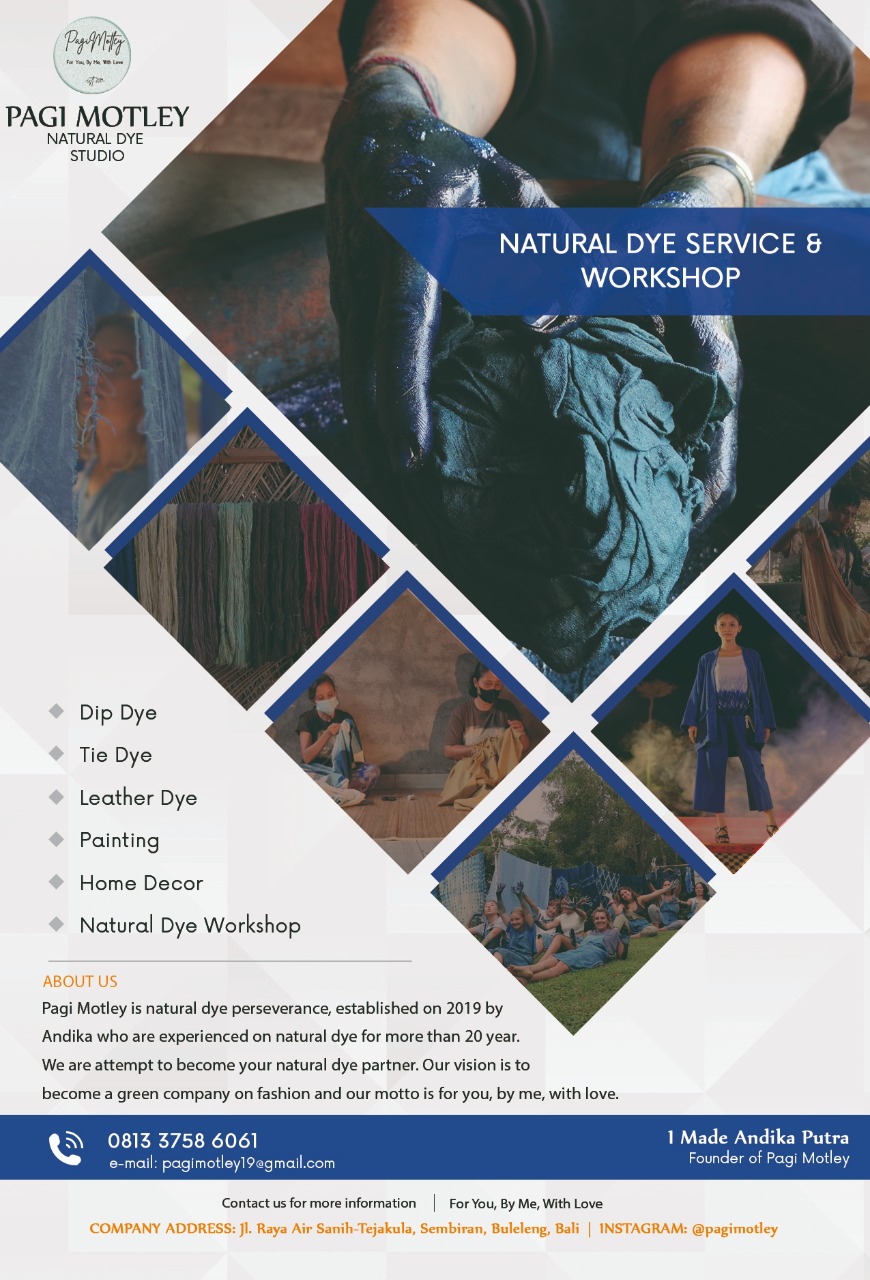

The problem of the disappearing ricefields is performed on the second festival day in a song called ‘Sawah’ by 9 North Bali artists who are concerned about the development. The way coconuts are carried forms the base for hand positions in dance performances: shoulders relaxed but powerful arms. Stomping in the muddy rice fields is translated to some of the leg movements you see on stage, writes Nyoman Budarsana.

Even the visitors who couldn’t understand Bahasa Indonesia enjoyed the artistic shows. Similarly, the students of the Ganesha University in Singaraja whose English isn’t good enough to write in, appreciated the space author Philip Cornwel-Smith gives them in his workshop to share their poems in their language.

Singaraja Literary Festival | Pic: SLF/Amri

This younger generation in Bali is no longer interested in becoming a farmer and much of the agricultural lands is slowly surrendered to the power of tourism capital. Should agriculture still be considered important by the Balinese? Or will the rural character become extinct? How can farming values survive or transform into a more popular form? Questions the festival seeks to answer in many of the panel discussions.

Other conversations take the theme more broader into the food that nature gives us as nutrition and medicine, and the ecological issues Bali deals with. The resilience of the agricultural world in the light of the increasing tourism industry, ecofeminism, and how literature can play a role in knowledge about water, the source of inspiration and energy on the island. The role of women in literature and ecology and the Anthropocene perspective on agrarian literature. And how not all ceremonial sequences in the lontar Dharma Pamaculan are performed because the instructions have become irrelevant in modern times.

Singaraja Literary Festivals seeks to connect old and new texts, ancient and modern times, and make sure to bring wisdom from the past to the future.

It shows in a moving tribute to Balinese feminist poet, novelist, playwright, and journalist Cok Sawitri who passed away in April. Her friends performed dance, poetry, and music to celebrate her work as one of Bali’s most influential female artists. “The festival shares the memory of friends and ancestors, who don’t need to be influential people to leave a legacy. People that leave a feeling in us are the legacy”, Sonia said after the performance.

Sawitri is also known for her activism, as someone who protested against mega-developments threatening the natural environment of Bali. She is quoted saying:

“I don’t like that the Balinese are only seen as exotic. Westerners too often misunderstand the Balinese because they are quiet in expressing their thoughts, or because they are not endowed with the logical and rational mind. However, the Balinese are intelligent and highly sensitive people. We have a different style and attitude, and code of ethics for public behavior. Often we do not communicate through words, yet via humor, symbols, stories, art, dance, and performance.”

Singaraja Literary Festival | Pic: SLF/Amri

The mix of Western and Asian views and opinions came to the surface in Mags Webster and Sally Breen’s Write What You Dare Not Say workshop. The writing prompts brought taboos on same-sex relationships, smashing the patriarchy, and being censored by Islamic fundamentalism to the table. It became clear that challenges regarding self-censoring for writers in The West or of a different level than their Indonesian colleagues, who not infrequently face serious consequences for speaking out.

Phillipine performance artist Nerisa del Carmen Guevara’s and Indian poet Sudeep Sen showed participants more subtle ways how to visualize and express a text in a performance. And poet Tan Lioe Ie showed them on the closing night how to. He was the first poet in Indonesia who used Chinese symbolic images in his poetry and this time he combined Chinese martial arts wushu with poetry reading, he roars and receives cheers from the audience.

A poetry slam competition with lines about Gaza and a surprising singing performance by author Dee Lestari close the weekend. As David concluded in an email afterward: “The festival feels like an enlightened hermit. Barely noticeable and draws little attention, but if you take the chance to engage with it, you may walk away with your soul filled, and mind enriched. [T]

Read other articles about the Singaraja Literary Festival

![Kampusku Sarang Hantu [1]: Ruang Kuliah 13 yang Mencekam](https://tatkala.co/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/chusmeru.-cover-cerita-misteri-120x86.jpg)